Loops in audio seem to confuse people, based on the questions that I get asked... The problem seems to be that people have got very used to a world in which looped audio is very common, but the way that it is produced is not very common. If you look at the humble WAV file as a multi-platform, generic way to store audio, then what it contains is just a digitised version of the audio. Playing back that file just reproduces the audio from the beginning to the end - if this was the previous century then a good analogy would be a tape recorder (or even a cassette recorder), where the audio is stored electro-magnetically on a long piece of magnetic tape.

Plain ordinary WAVs don't have loop points, but you can add custom 'chunks' inside the WAV file that add information about the loop points - Wavosaur or Endless Wav2 are just two examples of the many ways to add loops points that get stored as chunks in a WAV file...

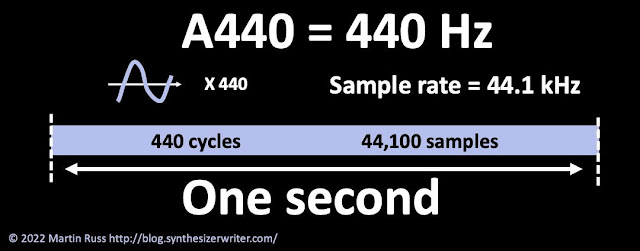

Most of the basic players that play WAVs just play the audio from the beginning to the end - because that's how most people are going to want to hear the audio inside the WAV file. The important numbers that you need to know are how fast the samples happen (so you know how to reconstruct the audio), and how many samples there are (so you know when to stop!). So for a short fragment of digital audio that samples the audio 44,100 times per second (CDs use this rate, for example), then a WAV file containing that one second of recorded audio is going to have 44,100 samples. In a minute, then that's going to be 60 x 44,100 samples (which is just over 2.6 million), and for an hour, then that's 60 x 60 x 44,100, which is nearly 160 million samples.

The 44,100 number comes from a requirement for digital audio to be compatible with the PAL and NTSC television systems - see this Wikipedia article for more detail. Sampling at 44.1 kHz means that the highest frequency that can be recorded is at just over 20 kHz, which is the highest frequency that young humans can hear (this frequency reduces with age, exposure to loud sounds for long periods of time, and other factors...).

|

| One second of digital audio |

In 2022, most of the digital audio that you will encounter in electronic musical instruments will probably have been sampled at at least 44.1 kHz (44,100 times per second), or 48 kHz, but some audio is sampled at higher rates: twice (96 kHz) and four times (192 kHz) the 48 kHz rate. If you are going to be working with samples, then that 44.1 kHz and time relationship is very important to know when you are trying to get your head around the length of samples, because it links the numbers of samples with time:

One second of audio sampled at 44.1 kHz is stored as 44,100 samples...

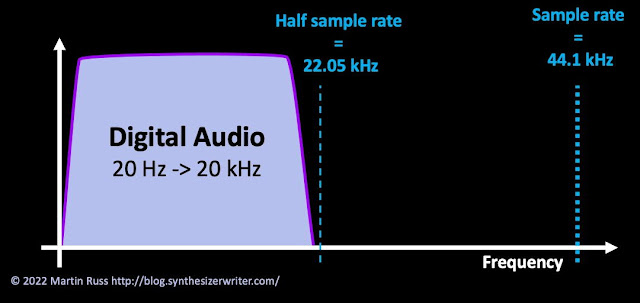

The resulting bandwidth is always less than half the sampling rate - see Nyquist, Shannon et al for more details. But basically, you need at least two samples to be able to reconstruct one cycle of an audio waveform, and so for a 44.1 kHz sampling rate, you can get a bandwidth from DC to about 20 kHz.

|

| Bandwidth is less than half the sample rate... |

It is worth thinking about the scale of digitised audio. A single cycle of 11 kHz (okay, a very high pitched sound!) will only contain 4 samples when it is sampled at 44.1.kHz, but it is also very short in terms of time. You need to zoom out about 11,000x to get to one second of time. You can see this when you are doing audio editing: When you have a few seconds of audio displayed on the screen, then you have to do a lot of zooming (tens of thousands of times) if you want to be able to see the individual samples in a waveform (and vice-versa).

|

| A single cycle is very short in comparison to time... |

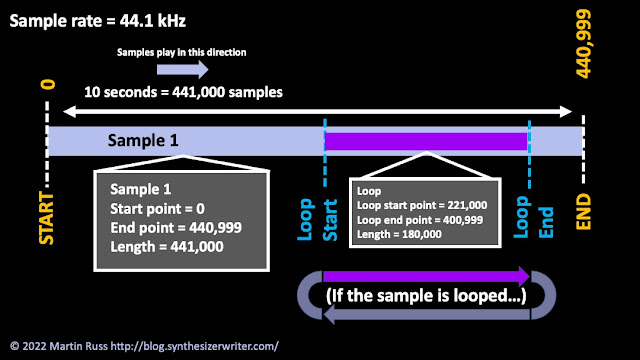

More sophisticated WAV players and samplers will need additional information beyond the sample rate and length numbers in order to provide more sophisticated control over the playback. One of the basic things that can be controlled is looping. At its simplest, a loop is just the same piece of audio, repeated over and over again. So a one second piece of audio sampled at 44.1 kHz will repeat every one second (1 Hz). But if you only play the last half of that one second, then because it is half as long, it will loop twice as quickly, and so will repeat at 2 Hz. In order to specify exactly what is meant by 'the last half', then we need some additional numbers: in this case, it is the start of the loop. Since we specified half way, then that is going to be 22,050 samples from the start. The end of the loop, in this case, is going to be at the end of the piece of digital audio, and so will be at 44,100 samples. So the numbers that specify this looped piece of audio will be:

Sample Rate: 44.1 kHz

Sample length: 1 second = 44,100 samples

Start of loop: 22,049 samples

End of loop: 44,099 samples

End of sample: 44,099 samples

If we wanted to loop just the middle part of the one second sample that we have been using as an example, then the start and end point might be 11,025 samples, and the end of the loop might be 33,075 samples. Note that the start and end points for the loop have to be 'inside' the total sample length, so those numbers can't be less than zero, or bigger than 44,100 in this case.

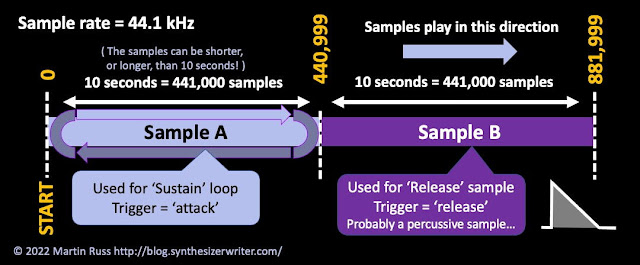

More sophisticated sample players can have additional loops - one use might be to produce audio when you release a key on a keyboard - known as the 'release' part of the sound. Again, you might want that sound to take a long time to fade away, and having a loop of audio means that you can have the long fade without having to store very long pieces of audio. The numbers used to specify where this 'release' loop starts and end would be known as the start and end points of the release loop.

|

| Loop start and end points have to be 'inside' the sample! |

Note that the release loop points also have to be 'inside' the total length of the sample. Also note that the sustain and release loops could be the same piece of audio, which would loop during the sustain part of the sound, and then loop again during the release part of the sound.

Without the loops, the audio in this example would play for just one second. With a sustain loop, then it would play for as long as the key was held down on the keyboard. For a release loop, then it would play for as long as the release time is set.

It is also possible to have 'attack' loops, where a portion of the audio is looped when a key is first pressed, and the sound goes from zero to maximum volume - this is called the 'attack' part of the sound. Some sounds drop down from that maximum to a lower 'sustain' level - pianos are a good example: they start out loud, but then slowly drop down to a quieter level. This 'decay' part of the sound can be produced using a 'decay' loop.

A sound recorded to use loops for the attack, decay, sustain and release parts of a sound could be very short in actual length, but the loops would enable the attack, decay, sustain and release times to be as long as required. In the 1980s, several manufacturers of electronic musical instruments used this way of storing samples so that the playback time could be changed (so you could have long attacks and releases, or long decays, or long sustain), but the actual sample lengths could be kept very short because the memory required was very expensive. Sample rates were also much lower in the 80s - 22.05 kHz was quite popular in some musical instruments and especially computers, and 11.025 kHz was also used (which will have an audio bandwidth of about 5 kHz - only slightly better than a telephone). The basic sample rate for telephones back then was 8 kHz, and the audio bandwidth was from 300 Hz to 3.4 kHz... not ideal for music! In 21st Century devices, storing long samples is not expensive, and so loops tend to be used mostly for the sustain and release parts of a sound.

It is worth reiterating that without loops, then digital audio replay happens without any flexibility of the length of the sustain or release time for a sound. It is only the widespread use of sample replay technology that has given us a world where an ordinary person expects that a sampled digital audio sound will keep playing for as long as you hold a key down on a keyboard. For people born before the middle of the 20th Century, for an electro-mechanical instrument like a Mellotron, which uses lengths of magnetic tape (not loops) to replay sounds, then it is obvious that the tape length has to be finite, and so you can only hold the keys of a Mellotron down for something like seven or eight seconds. In contrast, organs could (and still can) sustain a note as long as necessary, because the sound is generated inside the organ rather than being replayed from a stored (non-looped) recording.

Decent Sampler

Dave Hilowitz's Decent Sampler is a software sample player that can play back WAV files, and can play back sustain and release loops from inside those WAV files. The sustain loop start and end points can be specified inside the WAV file, or as part of an XML .dspreset file that Decent Sampler reads in order to know how to play the samples for a specific sound.

Decent Sampler is designed to read two different types of WAV file:

- multiple single WAV files containing a single sample, or

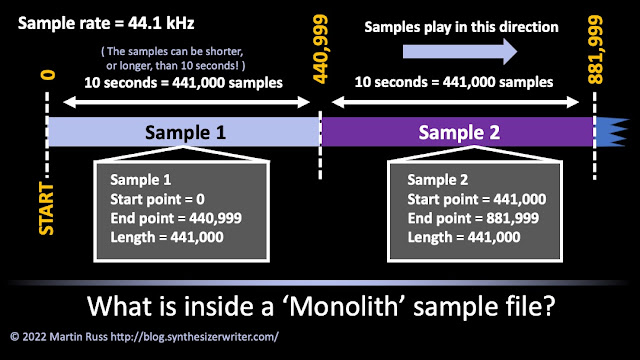

- one big continuous WAV file (made up of concatenated audio samples) where the WAVs inside are referenced as start points, plus end points. This is what Christian Henson (and Pianobook.co.uk) calls a Monolith file - you have a template on your DAW, and a voice track prompts you to play notes (on a piano, for example), and so you end up with a series of audio samples separated by silence (or whatever your recording system records when there is no audio, which probably is just the noise floor - so it is actually useful to have these gaps between samples because they are the raw material for Noise Reduction...), where the start point of each sample is gong to be close to wherever the voice prompt was (plus reaction time and any latency in the piano or synth...), and can even be partly or completely automated (do all of them assuming the reaction times and latency are going to be consistent). So if you look at a .dspreset XML file intended for use with a Monolith file, then there will be one sample file, and the start points will be the offsets into that file, whilst the lengths will be the length of each of the samples (minus 1). Yep, samples start at zero.

|

| Inside a 'Monolith' file |

Monolith files are great for people who want to automate as much of the sampling process as possible. So, if you want to sample a piano with a small interval (for example, thirds), how many velocity layers you want, how many beats you want to hold the note down (sustain time), etc., then you can use a template file that tells you when to play a specific note, and you just record everything as one large WAV file. The Monolith file that you get at the end has all the separate samples inside it, one after the other. There are various ways to edit files like this that enable multiple edits to be made at once, which can reduce the preparation time a lot!

Decent Sampler can also use .AIFF files...

The '1, 10, 100, 1000...' principle

For smaller projects, then individual WAV files can be used instead. If you have a Kalimba with 12 notes, then twelve sample files are pretty easy to manage. There's a principle called the '1, 10, 100, 1000 principle': if you are asked to, for example, sort 1 number into numerical order, then it is trivial - it is already in the right order. Sorting 10 numbers is going to take you a few seconds, but it won't be very difficult. However, sorting 100 numbers into order is going to take you a while, and you might not be very enthusiastic about doing it. But 1,000 numbers is rather different again - you aren't going to want to do it for free, it is going to take a while, and you will need to do some planning and work out a system to make it easy and reduce errors. A lot of people just don't want to do the 1,000 sort, and some are equally uncooperative about the 100. So 1,000 is some sort of built-in human limit. As for sorting 10,000 numbers, then almost everyone won't even start the sorting process without strong motivation of some sort (money, fame...)

So a project with more than 100 samples is going to need to be sorted into groups, which could be notes, or velocity layers, or some other parameter. Finding an approach that reduces that big number to something more manageable (like, nearer to 10-ish) becomes very important.

If you think about it, the Monolith system kind of hides the actual number of samples, or doesn't make the actual number quite as obvious because there's a single file with all of the WAVs inside it. And there are various 'do lots of edits at once' shortcuts that can be applied in a pro audio editor to make processing all of those WAVs easier.

How to Improve Noise Reduction...

|

| Noise Reduction |

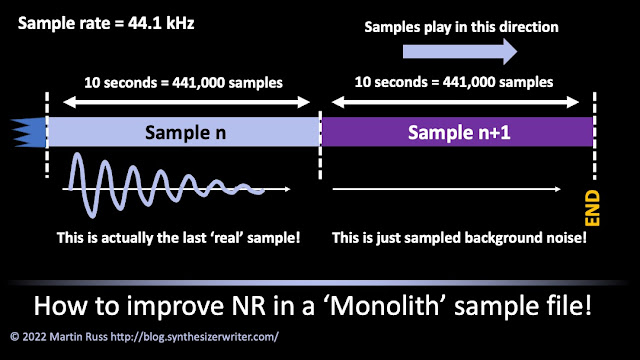

One thing that you can do with a Monolith file (or actually, any directory/folder of individual samples) to make it easier for you (or other people) to process it with a Noise Reduction Utility, is to record one extra sample - of nothing! Yep, just record nothing as the very last sample, and this can then be used as the 'reference' background sample by the Noise Reduction Utility. In a Monolith file, it can be the very last sample, whilst in a directory/folder structure of individual samples you could have a directory/folder called 'Background Noise' with a sample called 'Background Noise.wav' inside it.

When you record this nothing file, you should make it in exactly the same way as the previous samples, except that you don't play the actual note, hit the piano key, blow the trumpet, bang the drum, etc. But remember to record several seconds of nothing - this helps the noise reduction to work better. Also, don't adjust anything when you do this recording of 'nothing'. Don't turn the microphone you were using off, don't turn that buzzy light off, don't turn that ever-so-quiet fan off, don't turn the fridge off where you store the drinks, don't change any levels or EQ in the mixer or the audio interface... In other words, don't change anything from how you recorded the actual samples. What you want is all the background noise that is lurking behind the actual samples, so that the noise reduction can then remove it. If the noise reduction software doesn't have a good reference of what the background noise is like in your recording environment, then how does it know what to remove?

Inside Decent Sampler

I started out calling this section 'In Decent Sampler', but that doesn't read well! To control loops inside Decent Sampler, there are a few parameters that you need to add to the <group> element.

The basic <groups> element looks like this:

I have deliberately wrapped the text so that it works well on a narrow 'blog' layout! In a normal text editor, the lines of XML will be much wider, and without all of those line feeds!

The <groups> element is the container for all of the samples, which are in one or more <group> elements. All of the parameters that are in the <group> could also have been in the <groups> element, and then they would apply to all of the <group> elements inside the <groups> element. This time I have greyed out all of the parameters that are important, but not relevant to looping. So it now looks like this:

So you can apply parameters to either everything (<groups>) or to just a single <group> element.

You can have multiple samples inside a group, of course.

The relevant parameters for looping at the <group> or <groups> level are these:

|

| A one-second cross-fade... |

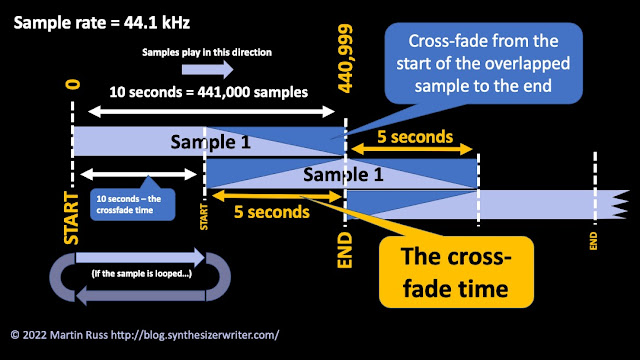

If the crossfade time is longer, then the actual time playing just the samples gets shorter and shorter. With a crossfade time of 5 seconds, we get five seconds of the initial sample, then a crossfade for 5 seconds, and then we immediately need to start crossfading back to the initial sample. So the only pristine bit of audio is the very first five seconds of the initial sample. Everything after that is just pure crossfade, all the time.

|

| A five-second cross-fade... |

If we wanted a cross-fade that was longer than 5 seconds, then we would need to overlap three samples instead of just two... (which can get complex) In most ordinary applications, the cross-fade is limited to half of the sample length. So for a ten second loop, this will be 220,500 samples, and since we need to subtract one because of the sample numbering starting at zero, then we would have a start of 220,499 samples, an end of 440,999 samples and a length of 441,000 samples.

So here's that XML fragment again:

Sample Lengths

If you don't specify the start and end of a sample loop, then Decent Sampler looks inside the WAV file for a chunk that specifies the start and end loop points. If it doesn't find that chunk, then it uses the start and end of the sample itself. If Decent Sampler doesn't know where the start and end of a sample or a loop are, then this can be bad. It seems that one of the problems with DS versions 1.5.0 to 1.5.5 was connected with start and end points...

One mitigation that I try to remember to use is to add the length of the sample (minus 1) to the end of all of the samples in the 'Samples' directory/folder. If I am going to be using looping then I also move some of the loop parameters into the sample element as well. So if we now look at the modified XML fragment:

It now becomes much easier to seer what the highest number that can be used for the end point is (440999!), but also keeping the cross-fade time below half of that is easy. Also, you can turn looping on or off 'per sample'!

Looping Samples for Sustained Pads

I'm now going to enter dangerous territory, because there are lots of ways of doing this, lots of opinions on the 'correct' way to do it, and lots of myths and pseudo-science. But this is what I do to prepare samples for looping - specifically, pad sounds. There can be a different approach for percussive sounds (I may have mentioned my big split of sounds into two categories: percussive and sustained?)

|

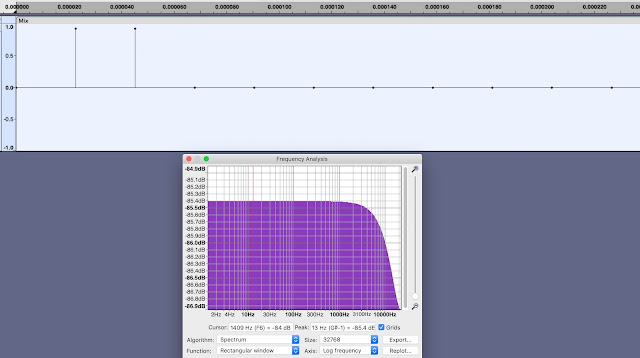

| A 'silent' loop join for a sound with 2 sine waves... |

So the above composite screen capture shows a waveform of two sine waves, slightly detuned from each other - see the DC bump in the spectrum on the left... The sample is 1 second long, and the two ends are shown in the two boxes on the right. So the loop 'join' is between the end and the start - in that purply-grey area. Note that both waveforms are at zero. If you were to print out the image, then you could cut out the two waveforms and they would join up smoothly across the join.

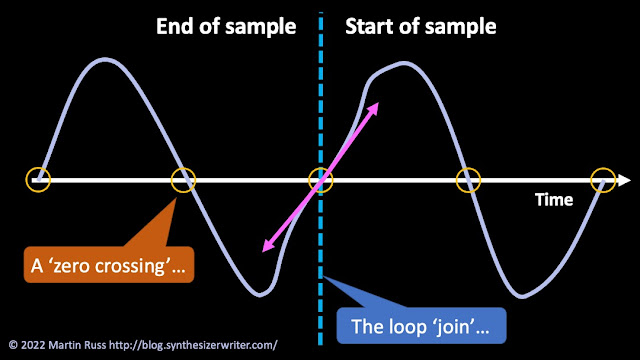

Ah, zero crossings. Not magic, and not special, imho, but... convenient. So below is what lots of people will tell you is how to do a glitchless loop:

|

| A 'zero-crossing' loop join... |

In this case, then both ends of the waveform are at crossing the zero axis (the horizontal line cross the diagram), and so have the same value. But this time the join is not smooth - there's a sudden change in direction: a discontinuity. Does this matter? Let's artificially generate a discontinuity and see what happens:

|

| A single discontinuity.. |

|

| A double discontinuity.. |

When the waveform is several seconds of zero, and then a maximum negative sample followed immediately by a maximum positive sample, then you have the worst possible mismatch of signals (+ to -), and this time, the spectrum is high frequency noise at around the half sample rate = 22.05 kHz.

So, sharp changes/corners in the waveform are not good. They create bursts of noise in the audio - which usually sound like clicks. So how do you get rid of these sharp changes or corners? You match the slope of the waveform at that point. Here's a diagram that shows, in bright purple, the direction (slope) that the waveform would continue in if it stopped bending as it passed through zero. it's a bit like a tangent to the curve at the zero point.

|

| Where do the waveforms want to go? |

As you can see, the end of the sample, on the right, wants to go upwards at a very steep angle. In contrast, the start of the sample, looks as if it expects the signal preceding it to be much lower. When they meet at the zero crossing, the mis-match of directions means that lots of frequencies are needed to suddenly change direction, and this causes an audible click.

Ideally, when two waveforms are joined, then the two curves should join up as if they were one continuous curve. Here's a diagram showing that:

|

| Waveforms going in the same direction at the join... |

Now the two direction arrows are going in opposite directions, and so not only is the join at the same voltage (zero), but the curve is smooth as well. This sort of join does not click. Well, it clicks a lot less!

|

| A fast-fade |

|

| Fast fades at the start and end of a sample... |

And that's how I join two waveforms. I do a fast fade out at the end (a few milliseconds), and a fast fade-in at the start (a few milliseconds). I also make sure that the slopes of the two ends are the same - pointing in the same direction. I also look backwards and forwards in time so that I make sure that the phase is opposite: a positive end connects to a negative start, and vice-versa. So the start is at zero, and the end is at zero, both waveforms are pointing horizontally, and the phases of the half-cycles either side of the join are opposite. What your ears hear is a cross-fade that is faster than the human hearing system can respond to (the human ear needs something like 10 milliseconds to detect an event), and so you don't hear anything. So there is very little to create a click, and your ears would not be able to hear it even if there was!

This is not a perfect solution to looping a sample! If the start of the sample and the end of the sample have very different timbres, then your ear is going to detect the sudden change of timbre at the loop point. For this, you need to slowly cross-fade (the time must still be less that half the sample length, of course!) from one sample to the other, so that you smear the change in timbre over time, and your ear will not hear it - because the timbre will be the same on either side of the join! When the timbre is similar on either side of the join, then you can do a fast-fade...

If you look at most of the samples that I use for pads in Decent Sampler, then they will have fast fades at the start and end, exactly like this. In fact, I do exactly the same for percussive samples, because if you loop a percussive sound, you do not want a click just as it loops! The only time that I don't use these fast fades is when I have a waveform that exactly fits into the sample length with an integer number of cycles. You can see this in the 2 sine wave example at the beginning of this section - the two waveforms are both at zero, and are both travelling in opposite directions, so the bright purple arrows would be pointing in exactly opposite directions, and so there is no need for a fast fade! The join is silent, seamless, and inaudible!

Some looping scenarios

Now that you know how to loop samples, here are some scenarios for using looped samples:

First, two samples used for the sustain and release segments of a sound:

Release samples are interesting. They are normally used for the sound made when the mechanics producing a sound stop - when you 'release' the key and let it go back to its quiescent state... In a piano, it is the sounds made by all the levers in the 'action' as they return to the default position, ready to propel the hammer at the strings when the key is played again. In a harpsichord, it is the sound made by the jack as it comes to rest against the string when you let the key spring back up. So these are often quite short, quiet sounds in real instruments - which doesn't mean that they have to be!

There does seem to be a limitation on the sort of envelopes that you can use for 'Release' samples in Decent Sampler. I have only been able to get AD envelopes to work correctly - it seems that the Sustain part of the envelope does not end, and so you never get to the release segment of the envelope. For most samples that you will use for release sounds, then this should not be a problem - just set the sustain to 0.0, and the decay so that it lasts long enough form the release sound to be audible.

So how do you control the envelope of a release sample? You probably don't need to have full ADSR controls in the UI, and maybe even no UI controls at all? Here's a quick fix - put the envelope controls inside the <group>:

---

If you find my writing helpful, informative or entertaining, then please consider visiting this link:

Buy me a coffee (Encourage me to write more posts like this one!)... or...

Buy me a coffee (Encourage me to write more posts like this one!)... or...

No comments:

Post a Comment